Planning for marketing planning: 14 steps to an effective presentation

Marketers always ask me for examples of my clients’ marketing plans. I can’t give you that, but I can tell you how to write a good one.

It is February. And that means that British marketers, all over the country, gaze up at snowy skies and then look forward to 6 April. That date marks the start of the new tax year in the UK and, by association, the day when many British companies begin their financial year too.

It is February. And that means that British marketers, all over the country, gaze up at snowy skies and then look forward to 6 April. That date marks the start of the new tax year in the UK and, by association, the day when many British companies begin their financial year too.

The reasons why 6 April, of all days, became the UK’s fiscal starting line are both complex and barmy. I won’t bore you with the story here – trust me its not column-worthy – but it’s a tale that includes Caesar, Pope Gregory, the solar calendar, leap years and the demands of 18th-century international trade. Suffice to say, the British eventually landed on 6 April in 1800 and have steadfastly maintained it ever since.

The relevance of all of this for marketers is considerable. While many companies, especially international ones trading in the UK, operate on calendar year plans or other strangely aberrant schedules, most British companies still operate from April onwards. And that means that marketing departments need to have their strategic and tactical shit sorted by then. Which is why February tends to be the pointy end of the planning cycle for many British marketers: they have eight weeks to get a plan together.

Well organised marketers working for well run companies should, by now, have everything squared away. One of the secrets of good marketing planning is to get the work done ahead of the finance teams, so that marketing can propose its budget and have an input into the sales projections for the year ahead. That approach is infinitely superior to waiting for the CFO to estimate everything using arbitrary guidelines and then allocate marketing’s crumbs from the top table, while operating under the overriding assumption that marketing is just another cost, like office toilet paper or heating bills, that needs to be allocated.

The dumb reality of most British marketing planning, however, is that this sub-optimal, cost-based, marketing-as-a-proportion-of-expected-sales approach is exactly how most marketers derive their budgets. And there is very little they can do about it. February usually marks the final allocation of budgets at most companies, meaning marketers are currently being tasked to come up with their marketing plan for the year ahead because 6 April is now looming into view.

The marketing plan. Is there a more important or ubiquitous topic in marketing that has such incredible levels of discomfort and uncertainty attached to it? I must be asked at least 20 times a year by marketers if I can send them a copy of a marketing plan that they can take a look at. That’s tricky, given most clients I have worked with aren’t especially keen on sharing these documents with their colleagues, let alone clueless strangers.

But it is something that I can very definitively write about. I have helped build, present, critique, demolish and execute thousands of marketing plans in my career. That last sentence is not hyperbole by the way. One of the requirements of consulting for large global companies is that you help them structure and then review hundreds of plans. I have several clients that I have worked with for many years. Each has between five and 20 major brands. And each operates in 20 or 30 key countries. Run the numbers and you can see why I have spent a significant, and not unrewarding, part of my professional life on marketing planning and marketing plans.

So, for all you marketers staring blankly at a patchy Powerpoint deck that is meant to be a completed marketing plan, here is everything that I can tell you about how to build a decent marketing plan.

Three axioms and three questions that summarise all of brand strategy

Marketing plan or brand plan?

There is no consistency out there in the world of marketing to delineate between brand plans and marketing plans. Many younger marketers assume there are fixed rules, to which they are currently not a party, that nut all of this out in gratuitous detail. Trust me, no such guidelines exist. The practical reality of planning is that marketing plans and brand plans usually mean the same thing. The title you use comes down to the brand architecture of your company and not some hard-and-fast procedural rulebook.

In companies that lean to the ‘house of brands’ side of the brand relationship spectrum – the P&Gs and LVMHs, for example – marketers usually work on brand plans. On the other side of the spectrum, at companies that are closer to a ‘branded house’ approach – think HSBC or IBM – the focus is more likely to be an overall marketing plan for each key country. Titular differences aside, there is no meaningful difference in the content and flow of these two documents. They cover the same ground and this column could just as easily have been titled ‘Planning for brand planning’.

Twelve-month increments

Before you even start on your marketing plan you must first lock down the time period that the marketing plan will encompass. My strong recommendation is that you plan in 12-month increments. Ignore the agility junkies who reject the need for any plan or demand something shorter-term. Of course, a strategy will always deviate as events unfold in unexpected ways. You need agility. But it does not replace the requirement of an initial strategy, from which to deviate in an agile manner.

That agility will be sparked by unknown events that will occur down the track, but strategy demands an a priori approach that pre-exists and predicates the nimbleness. A 12-month marketing plan is just as important for those who promote agility as for those aiming for consistency.

Beware also those who push for a three- or five-year marketing plan. While product development and corporate finance legitimately often require a multi-year approach, marketing works best on a 12 month planning cycle. I’ve seen my fair share of three-year marketing plans. They involve a lot of planning for the coming 12 months, and then a simple extrapolation for the following two years. It’s an abstraction that renders all multi-year marketing plans much less valuable than a 12-month version.

That does not mean your strategic vision needs to end abruptly after one year. You can certainly plot out a multi-year journey for your brand. But eat the elephant one bite at a time and project forward only the first year of that journey. Your objectives might have a long-term direction but you can write them with a 12-month goal in mind. Then review and revise as the years unfold.

Twenty slides, 60 minutes

Most marketing plans are Powerpoint presentations. Nothing wrong with that. But they are just too damned long – 50, 100, 200 slides in a plan. About half of the marketing plans I have seen presented end with the immortal words: “Well, I am conscious of time so let me skip to the conclusion.” This is a shithouse way to present anything. It is symptomatic of global marketing teams with no practical experience of brand planning, who are just building Powerpoint decks by the yard. And it is indicative of marketing managers who have not thought long or choicefully enough about their plan.

Learn to kill the extraneous and say in one bullet point what a McKinsey consultant would need a report and £320,000 to deliver. If you cannot organise your marketing plan in such a way that it be communicated in 20 slides and 60 minutes, you are almost certainly too disorganised to execute it down the track. Twenty slides plus the judicious use of hyperlinks (we will get to this point later) is the only way to roll. And if you can do it in 15 slides and 40 minutes, even better.

The marketing triptych

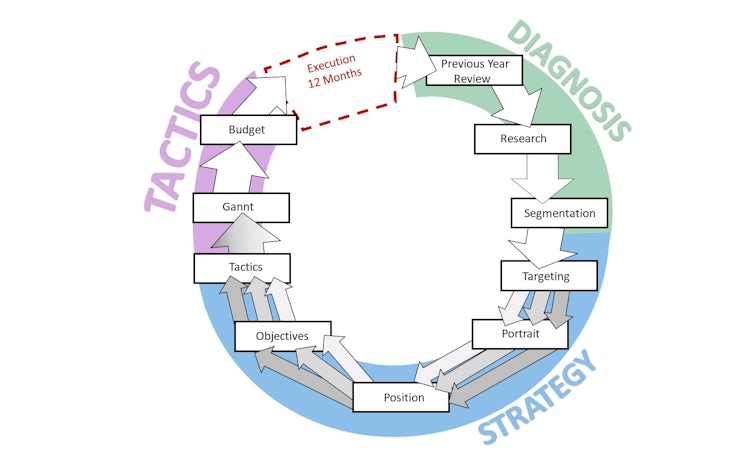

Marketing and brand planning work through three sequential phases. First, we diagnose the situation using data. Second, we put together a strategy. Third, we plan the tactics that will deliver the strategy and success in the market. Then, all things being cyclical, it is back to a new diagnosis the following year to see if the strategy worked and start the process again.

A good marketing plan will follow these three phases in its structure. Diagnosis should lead to a strategic section and finally to tactics and the budget associated with them. There is no single ideal marketing planning format. Every young and desperate marketer searches online and in vain for a magical standard template that you fill in the night before the big presentation day. But Google rewards you with 100 dumb-ass versions of different stupid plans. No standard exists. And each company should and does riff on the design to create their own gold standard. But this overall three-part structure of diagnosis feeding strategy, which drives tactical choices, is inarguable if you know what you are doing. Try and stick to it.

Start before the beginning

The best marketing plans start by closing the loop on the previous year. The shape of all marketing planning should be circular – see my tasty little diagram above. (I do all of these myself, you know. Can you tell?) That means the very first slide after the title should be a summary of the objectives that were set in the previous year’s plan, with an update on whether they were achieved and why.

This achieves four important ends. It concludes last year’s plan. It demonstrates key lessons and learnings from the year just gone. It provides the context for the new year. And it supplies the benchmarks to build from in the new plan that is about to be presented.

If you have not yet set any objectives for the brand or you are new to the role, you can skip this section. But nothing connotes you know what you are doing more than pulling up last year’s objectives at the start of your presentation and rattling off whether they were achieved, with a pithy explanation for each. Don’t fear the objectives you failed to achieve. There is nothing more comforting for senior management than a marketer explaining why they screwed up with the kind of insight and humility that suggests they won’t make that same mistake again. It’s almost (almost) as good as achieving the objective.

Research without the detailed insight

It is crucial to build a marketing plan from fresh data, and not assumptions or outdated insights from a market that has changed significantly since the research was collected. But one of the most common pitfalls of bad marketing is to use up most of the presentation of the plan on excruciating, extraneous detail about market research and what it revealed about the market.

This is not an insight session. This is market planning. Your insights and findings should, ideally, be baked into every slide in your plan. Don’t waste too much time sharing survey results or focus group quotes. I recommend a single slide that lists all the research that was used to build the plan and maybe a line on the key insight or rationale for each piece of research.

Marketers love talking about their data but no-one else gives a shit. An important insight is that the budget slide is literally 10 times more important than the insights slide. The research is the foundation for you plan, not the plan. Move quickly here.

Segmentation is the end of diagnosis

One of the great errors of market segmentation is thinking that this step is somehow about you or your company. The clue is in the name ‘market segmentation’. It has nothing to do with your organisation and everything to do with the market. That means, in theory at least, your competitors could build exactly the same segmentation as you. Segmentation is not strategy, it is a map of the market and therefore part of the diagnosis. You should be using your data to build an updated segmentation model – no targeting yet, just an overview of the whole market.

A few tips here. First, get the whole segmentation onto a single slide. Playing chess across multiple chessboards is beyond most of us. Second, make sure your segments have a name based on behaviour (not targeting), a population size, a value and your estimated market share. Don’t add anything else other than these four things. It confuses everyone if you do. Finally, make sure your data is up-to-date. A good segmentation should not change from year to year in a stable market. But the sizes of the segments and the shares of each segment owned by the different competitors will change – hopefully because your previous strategy made them change in your favour. You need up-to-date information to ensure your map of the market, on which your strategy is about to be built, is accurate.

Where will you play?

If segmentation is the map of the market. Targeting is the time to plan how you will traverse it. That means targeting, in direct contrast to segmentation, is about your company and its brand and its resources. Targeting is the start of strategy. Be selfish here. Remember that two-speed targeting not only allows but impels an approach in which you aim at the whole market for the long term, top-of-funnel brand-building and then multiple targets for the short-term, lower-funnel activation stuff.

We need a new ‘third way’ to set marketing budgets

To decide whether you target the whole market and/or some of the segments, you need to return to your segmentation in your presentation and overlay your targeting choices on top of it. Expect a debate in the room at this point.

A crucial area for many plans is whether to target defensively to maintain share in segments where you have good penetration already. Take care here. Sales teams love revisiting loyal customers. It’s an easy, very pleasant and usually successful sales call. If this customer would have ordered from you anyway without the call, don’t target them and aim your resources at harder, more incrementally valuable customer segments.

Remember to be choiceful here. You do not have unlimited resources and the segments are differentially valuable. Beware any marketing plan that goes after all the segments. Or which lists all of them as priorities from one to 10. Focus on where you can win, where the wins are big and where the victory fits within the broader remit of long-term business strategy. And then take pride in the segments you won’t go after and the rationale for their avoidance.

I always encourage marketers to structure their plans from targeting onwards as a series of ‘arms’ – shown as three separate arrows in the tasty diagram above. Having explained the first target segment and your strategy for it, return to the original segmentation slide, remind the room of the overall market, locate and identify your next target, and start a new arm of the plan.

Miserable portrait

Personas and portraits get a lot of shit. Rightfully so. They are usually built from abject nonsense and usually reflect the fictional aspirations of the marketer in question, rather than the empirical reality of the market. But a proper portrait is a very useful thing. Take the quant results from your survey and the best qualitative insights from your focus groups and build a picture of this customer segment. Who are they? What turns them on? What turns them off? What do they currently do in the category? Why do they do it?

A fictional, horseshit portrait is a marketer’s wet dream. A photo stock image of a beaming model sits above a paragraph describing someone who likes your advertising, loves innovation, is a big brand loyalist and cannot wait to try your new product. Authentic, superior portraits are depressing and confronting slices of reality complete with miserable quotes and disappointing data points. There is a reason we are targeting these customers. Your portrait should capture the challenge. Tell the truth.

Onion-free positioning

Most marketers don’t understand positioning. They have turned it into an over-indulgent, complex wankathon complete with layer upon layer, brand books and a plethora of meaningless words like innovation, quality and integrity. Positioning is just the intended brand image. It is what we want the target consumer to think when they think about our brand. And, if you are lucky, you might have two or three brain cells at best to work with. So keep it simple and keep it old-school.

Your plan has explained which target you are going after and, via the portrait on the previous slide, who they are and what they think. In your positioning you just need to outline three things. First, ‘what’ you will be positioning to this target. Second, ‘versus’ which competitors or alternatives. Third, the ‘is’ – what you want the target consumers to think. Take your time on all of these three questions because they are a lot more complex than you might initially think.

The ‘what’ is a far trickier question than it appears. In some cases you want to position the brand, sometimes the company, sometimes a specific product line and occasionally a more general concept such as doing business in a different way.

The ‘versus’ is also tricky. Just as the customers in a segment are different from the mass market, so too are the alternatives that this segment is considering for their purchase. Be market-oriented here and don’t list the generic competitors in your category. Instead, ask your segment for their options. Don’t even use the word competition. These are the alternatives as seen from the customer’s perspective, and many of their nominations will come from outside what you thought of as the category. Before you go to war, make sure you know who the enemy is.

Finally, make sure your ‘is’ passes the classic ‘three Cs’ test of positioning. The two or three words or phrases you land on should be what this customer wants (check their portrait), what we can deliver (check our product), better than or different from the alternatives (check the ‘versus’).

Pointy objectives

Your marketing strategy is getting there. You’ve picked a target. You’ve worked out what you want to position to that target. The final part of the strategy section of your plan is to outline what you intend to do to this target. Obviously, the ultimate goal will be sales and profit. But to get there, which marketing lever do you need to pull? Do we need to make this target aware of us? Should they consider our brand? Prefer it? Buy it more often? Buy it again?

A good marketing plan uses a funnel and the comparative conversion rates of its brand versus competitors to isolate the weak or opportunistic step to aim for with this specific target group. The plan uses that information to set clear, pointy goals for what it will achieve over the coming 12 months. It might be an undergraduate insight but most marketers simply cannot write a proper objective.

You can spot shit marketers a mile away because they have SWOT, Maslow and PEST in their plans and an array of fluffy, anodyne slogans that they have confused with proper objectives. Pointless tools from worthless marketers. You can identify good marketers because they have SMART objectives rather than vague, unmeasurable aspirations.

Remember your marketing plan probably has multiple targets and each will need objectives so be choiceful here too. The best research from the corporate strategy world suggests a handful of objectives for the whole plan is ideal to achieve executional success. Any less and you will not achieve enough, any more and you will spread yourself too thin. So, keep it tight here. A single SMART objective per target is invariably the way to go and, unless you’re Amazon or P&G, three or four for the total plan works best.

Tactics

You are on the home stretch! While tactics mark the third and final stage of the plan I would still split them per target. The best way to do this is to list the objective you have for each target and then beneath it the tactics you propose that will deliver the strategy in the year ahead, along with estimated costs.

Ideally, once you have been through all the targets and all the arms of your marketing plan you can summarise the total tactical picture on a single Gannt chart. Again, it’s old-school but nothing conveys the tactical plan better than everything splayed out across a big fat Gannt. You can then read horizontally to look for synergy and interactions across the tactics. And then read vertically to check that the marketing department is not overly stretched at certain points of the year when too many tactics take place too close together.

Budget

Finally, we get to the most important slide of them all. I’ve sat next to general managers, divisional VPs, even the odd CEO during a marketing plan presentation. Trust me – they can hardly keep their eyes open during your amazing segmentation or passionate explanation of positioning. But when we get to the budget slide everyone of any importance gets super fucking interested, super fucking quickly.

Senior management hire people like me to sit next to them and check the veracity of your plan while they sit through your presentation waiting for just two pieces of data. How much is this plan going to cost? And will this plan deliver the top line I was expecting to allow me to hit my numbers?

The fascination with the budget slide from senior management is in stark contrast with the investment of time that marketers put into this section of the plan. In many cases the numbers simply do not add up. And even if they do, they all too often make no sense. The message should be clear. Get these numbers right. And be ready to explain and defend them to the hilt.

Any decent middle manager is going to test you by asking if this budget could be reduced somewhere and still achieve its stated return. Push back respectfully and don’t ever break the hopefully legitimate connection between what you want to invest and what you think you can return. If your boss wants you to spend less you have to concur. But you also have to revise the expected return accordingly. Or your budget is bullshit and you are too.

Remember that, while most companies agreed their marketing spend for the coming year long before you started working on your plan, they have not allocated it yet. If your plan is better, more ambitious, more likely to transpire than that of your peers presenting after you, there is every chance senior management will take money from them and invest it with you instead. Like the man slipping on his running shoes when he and his mate bump into a leopard in the jungle, you don’t have to beat the whole budgeting system of your company, just have a better plan than your shit colleague. And don’t feel bad about it either. Fuck them. Efficient capitalism dictates that marketing money should go to the best marketers with the best plans.

A last point: hyperlinks

This tight format for your marketing plan will inevitably remove many of your best slides and some important observations. The place for this material is at the back of your deck linked to the marketing plan via a simple hyperlink that Powerpoint enables you to drop into any slide. If you expect a challenge on why you are not targeting the ‘Big and Lazy’ segment, put a link there to the survey chart showing how loyal they are to a rival firm and put a return hyperlink on that slide back to the main deck.

If a skeptical sales director or annoying marketing professor challenges your approach you can then click quickly to the slide, make your point, spank everyone that ever doubted you and get back to the plan. This tip achieves more than just expediency. It sends a signal to senior management that not only can you answer any question, you’ve anticipated it, prepared for it with data, and are waiting with a massive bear trap and spear gun for anyone dumb enough to actually ask it. You’re signalling to every fucker in the room that you have got this. This is your plan. Back off.

Senior management, confident in your abilities and sick of falling into different bear traps, sit back and let the plan flow from that point. Hyperlinks are a little thing but they make big impression. If you click on the one below, for example, it will take you to a whole new level of marketing capability.

Mark Ritson teaches this and many other things in the Mini MBA in Marketing this April.