‘Funnel juggling’ is the answer to marketing effectiveness

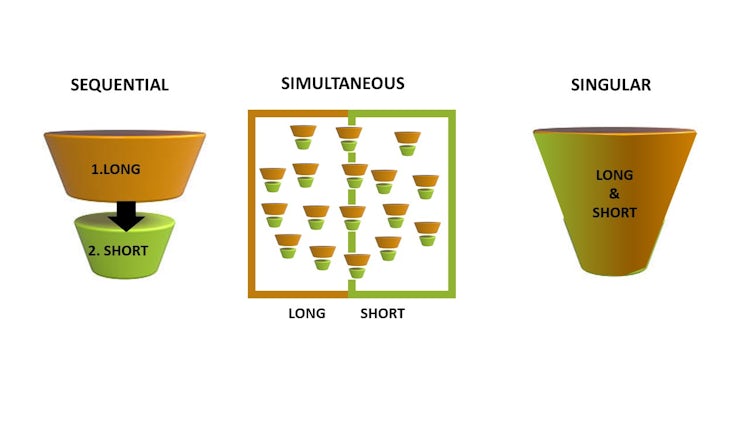

It’s well established that brands need both long- and short-term marketing to be effective, but you’ve still got to decide between the three options for how to use them.

How has this long, strange period of Covid-induced change been for you? It’s been an odd one for me. I spent the first few months of 2020 doing what I have done for over a decade: getting on planes for 10-day jaunts working for brands and the people that manage them.

How has this long, strange period of Covid-induced change been for you? It’s been an odd one for me. I spent the first few months of 2020 doing what I have done for over a decade: getting on planes for 10-day jaunts working for brands and the people that manage them.

The first few days of March ended up being my final week of that ‘normality’. I flew to London, Tallinn, Oslo and then Reykjavik, and then circled back via clients in Brisbane and Sydney. I landed back home, watched the travel ban coalesce all around me, and have not been on a plane since.

All that flying was obviously very labour-intensive. But being in a client’s office, having a beer with them in the evening, seeing them in their natural habitat, always added so many extra levels of insight. If I could put a number on it I would tell you that about 50% of the consulting job happened in the allocated sessions in HQ and the other half in cars, bars and around the back of a restaurant smoking cigarettes in the snow.

I worked for a large Swiss brand last week and, prior to the virtual meeting, the senior marketer showed me the view out of the boardroom window of the lake and the late-summer Swiss magnificence surrounding it. I must confess I felt a pang of regret at not being there and having the direct, physical experience of learning from and working with others. But then the clock struck 9am and virtual faces started to pop up, and we Zoomed off into the meeting.

I still work for clients, but now in my underpants with a dog, sometimes two, snoring at my feet. In the brave new Covid-afflicted world of consulting, a good home internet is essential but trousers are optional.

And, aside from riding bareback through countless engagements, there are several other pros of this suddenly different way of working. The lack of air travel and jet-lag has done wonders for my health. My family are immeasurably happier to have me at their beck and call too. And the number of clients I now engage with has increased because, with travel time eliminated, I have more face time for more brands.

That increase in client interactions and faster, more immediate access to their challenges has opened my eyes to one new glaring issue for good brand managers operating in latter half of 2020. And it has nothing to do with that pesky virus or the myriad implications that arrived along with it.

Watch: Ritson’s nine marketing effectiveness lessons

While marketing in general has been obsessed with the impact of the coronavirus and the subsequent recession that follows it, the bedding-in of long and short thinking for most advanced marketers appears to be almost complete. In the last two short years, ‘The Long and the Short of It’ authors Les Binet and Peter Field have been established, along with the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, as the originators of the most accepted theory in brand building. It is nice to see how the hard work, advanced empiricism and tub-thumping for the two ‘godfathers of effectiveness’ has finally borne fruit. Not just in their sudden fame but also the impact their work is having on countless brands.

But with acceptance comes more advanced issues of application. And while I see a ton of companies now working with the concepts of long and short, there is a significant challenge in turning theory into praxis. Specifically, a lot of marketers are struggling with funnels.

The funnel is the backbone for good marketing planning. And a decent marketer not only has a funnel, they have customised the steps in that funnel to their own specific customers. They have measured the steps and conversion rates from stage to stage and compared these numbers to their competitors. And – if they are really good – they have a very solid dashboard featuring all of this, thus enabling the team to monitor what is and isn’t changing as they pull the brand’s tactical leavers.

As useful as this is, however, the funnel has some drawbacks. At the end of the day the whole metaphor is decidedly vertiginous and linear in nature. You move from the top to the bottom. In sequence. And that has led many marketers to design their marketing that way too.

In some cases this approach leads to executions that are technically correct on paper, but less effective in application. The presence of a funnel is always a sign that you are working with a well-run brand. But how that funnel is used to originate strategic and tactical activity is also a significant, further indicator of brand expertise. Specifically, there are three ways to juggle your funnel.

Three approaches to ‘funnel juggling’

1. The sequential approach

This is the most literal interpretation of the funnel. A brand focuses on the top-of-funnel, emotional messaging and builds brand equity first. Then, with suitable amounts of awareness and positive affect in place, it exploits those advantages with targeted, product-based offers that convert all that brand equity into growth and incremental sales.

There is a superb case study in Australia at the moment. Insurance brand NRMA has a wonderfully clear brand position based on ‘Help is who we are’, featuring everyday Aussies helping others. When Covid-19 lumbered into view, NRMA’s customer acquisition – like that of most insurers and many other companies – started to fall off a cliff as toilet paper replaced car insurance in the minds of most consumers. That sudden dip in demand saw many companies drop price and switch to promotional marketing to try, and usually fail, to drive revenues.

NRMA’s CMO, the appropriately named Brent Smart, took a different approach. He realised there was little point in running the usual short-term insurance campaigns when the market was no longer interested. Instead, a brand that was positioned around help should communicate that message clearly to its target customers. That made a lot of sense when media companies were offering such good deals on inventory and many rivals had gone quiet.

Smart shifted all his marketing money for Q2 into long-term brand building and then went upstairs to ask for even more. While others were pulling back, NRMA upped their media budget by 68% for the first three months of the Covid crisis and spent every penny on emotional, top-of-funnel, long-term brand building.

Crucially, while the budget changed, the campaign’s creative theme did not. Many brands paused their long-running advertising campaigns in March for bland, ineffective statements of support accompanied by twinkling pianos and grandmas beaming at their grand-kids via Skype. Smart did not want to throw the branding baby out with the Covid-19 bathwater.

Using existing footage from an earlier brand campaign, an ad was created in which a young boy who had rescued a koala in an earlier ad was now shown in lockdown with his mum. Grizzled Aussie icon Jack Thompson added a reassuring voiceover and the ad was launched on 29 March. It had taken NRMA just 10 days to increase budget, reassign media choices, and create and launch their new campaign. Agility is not hot-desking and an unintelligible org chart.

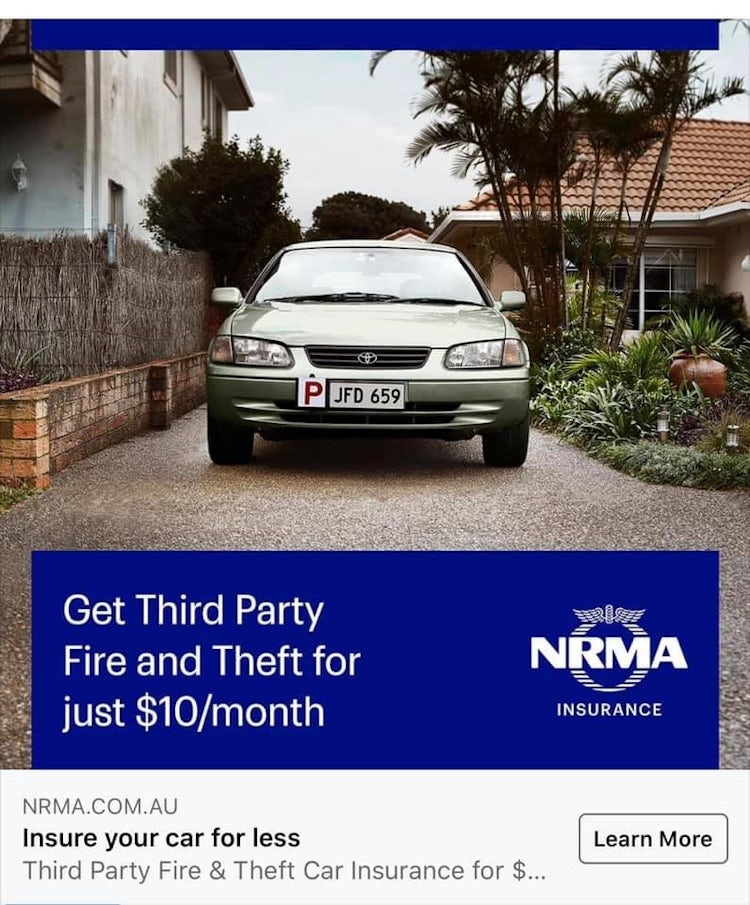

As Q3 approached, consumer data suggested normality was starting to return. Anticipating that many customers would be forced to cancel their existing insurance policies in the face of an inevitable recession, NRMA launched a simple $10-a-month ‘third-party, fire and theft’ policy for those who were worried about money but still wanted some peace of mind. The new NRMA campaign was launched in a very different fashion. It was a classic short, performance-marketing execution. A very targeted approach, using mostly digital media, with a specific product offer, and a very clear call to action.

Like all good ‘short’ marketing, and unlike its ‘long’ and more elegant sister, this work could be held directly accountable to ROI calculations. In NRMA’s case the company sold 13,000 of these policies a week during Q3, compared to the 3,000 they usually manage. The success was partly down to a very agile bit of product development and an attractive price point. But only a fool would dismiss the value of the long work that set things up during the three months prior to the offer. Running it long and then short can be a powerful approach.

Like all good ‘short’ marketing, and unlike its ‘long’ and more elegant sister, this work could be held directly accountable to ROI calculations. In NRMA’s case the company sold 13,000 of these policies a week during Q3, compared to the 3,000 they usually manage. The success was partly down to a very agile bit of product development and an attractive price point. But only a fool would dismiss the value of the long work that set things up during the three months prior to the offer. Running it long and then short can be a powerful approach.

2.The simultaneous approach

Covid-19 provided NRMA with the perfect storm to run just long communications for several months and then benefit from activation once the market started re-enter the category. But in many cases there isn’t a single funnel with the market marching down it in lock-step like a terracotta army. Instead, customers are distributed all over the place. Some have not heard of your product. Others are actively considering it. Others are buying it on a regular basis.

Given this consumer diaspora, it often makes more sense to devote resources to both long and short marketing activities in a separate but simultaneous fashion. The fabled 60/40 rule about the proportion of budget to invest in each might still be guiding the execution, but that money is being spent at exactly the same point in time – often with different agencies and usually with very different media choices.

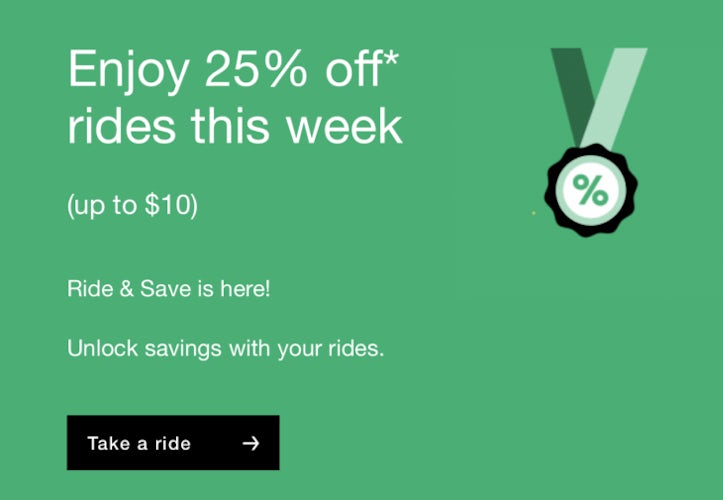

Take the impressive advertising for Uber. It has always been my go-to case study when someone asks for an example of the difference between long and short. I always turn to the ride-sharing firm because they clearly get it right and execute it beautifully.

For the long work, in most Uber countries there are a series of brand campaigns that push the emotional benefits of travel. Inevitably and rather cleverly the focus is on the top of the benefit ladder; or, in Uber’s case, the end of the journey, when it delivers you to your destination and the emotional benefit that awaits. In the US, for example, the brand uses TV, outdoor and digital media to associate Uber with these moments. It’s mass-market, it’s emotional, it’s brand-focused and it asks nothing of the consumer other than to see Uber as more than a ride-sharing service.

For the long work, in most Uber countries there are a series of brand campaigns that push the emotional benefits of travel. Inevitably and rather cleverly the focus is on the top of the benefit ladder; or, in Uber’s case, the end of the journey, when it delivers you to your destination and the emotional benefit that awaits. In the US, for example, the brand uses TV, outdoor and digital media to associate Uber with these moments. It’s mass-market, it’s emotional, it’s brand-focused and it asks nothing of the consumer other than to see Uber as more than a ride-sharing service.

I have no idea what the split in Uber’s marketing spend actually is but I will bet about half of the money in any country also goes on the short of it. In this case, much more targeted, service-based messages that present a very specific offer to a very particular segment with the aim of delivering on an explicit strategic goal. Perhaps it’s an online voucher to encourage lapsed riders to use the service again. Or maybe an introductory offer to get first-timers to take their first ever Uber. The point is that this is short, performance-based sales activation. And it is circulating at exactly the same time as the brand-building media campaigns.

Executing a long, mass-targeted ad that also features short, targeted product messages would be hard to pull off without it looking like a dog’s breakfast of an ad. But running both long and short approaches in market simultaneously allows Uber to create top-of-funnel attraction and convert it with bottom-of-funnel sales.

Executing a long, mass-targeted ad that also features short, targeted product messages would be hard to pull off without it looking like a dog’s breakfast of an ad. But running both long and short approaches in market simultaneously allows Uber to create top-of-funnel attraction and convert it with bottom-of-funnel sales.

Some of that synergy might happen at almost exactly the same time – a businesswoman sees a big outdoor ad for Uber on the way out of the airport. She then sees her voucher for a free ride and activates it. Or, more likely, the long throw of the fishing net across the whole market provides a general impact that the shorter-term activations then attempt to bounce off. Both long and short are executing at the same time, even if the consumers and the approaches are radically different.

3. The singular approach

But there is a third way. The great market researcher Ken Roberts makes a very coherent argument for singularity, and delivering both long and short effects within the same tactical execution. Roberts does not challenge the value of the long and the short of it, far from it. He has seen first hand in his own client work the effect it can have.

But he is less sure about the idea of separating these two objectives into distinct campaigns, often executed by different agencies. “Is it optimal,” he asks in a recent monograph, “to have brand-building communication without activate-now? Or activate-now communication without brand-building?”

His question derives from two equally important insights. First, if we subscribe to the ‘system 1’ and ‘system 2’ processing metaphor of Daniel Kahneman and the army of marketers that follow him, then this separation of long and short is unnecessary. Automatic, intuitive system 1 thinking can and will happen at the same time as considered, rational system 2 thinking takes place inside the customers head. Why, then, split up the campaign, when a psychological BOGOF is not only possible, but preferable? Build brand and drive the consumer to buy in the same ad.

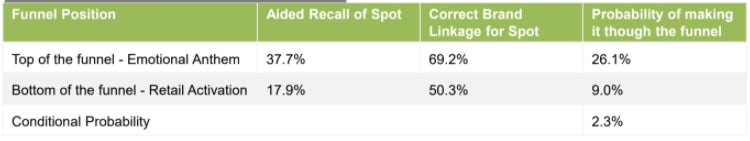

And Roberts makes a further argument in favour of the singular approach. He points out the piss-poor performance of most advertising when it is held accountable with the two most important basic metrics of effectiveness. First, does the consumer remember the ad? Second, do they link the sponsoring brand with that ad? You need both in order to have effect, and yet most data suggests that only around 20% of campaigns are both remembered and then correctly associated a day after exposure.

That’s a scary stat at the best of times, but when you contemplate its implications for separate long and short campaigns – working separately but in tandem, in either the sequential or simultaneous approach – it becomes positively horrific. Roberts uses the example of a client of his that achieved a 26% success rate for the long, emotional, brand-building campaign and then a paltry 9% for the simultaneous retail activation.

These are disappointing but not unusual statistics. But for the long and short to work its magic we need to combine them and look at how many people in the target audience successfully recalled and associated both the brand and activation campaigns: 9% of 26% is just over 2% of the market. And even that tiny figure is based on the assumption that these recall scores do not decay – as we know they must – over time.

Roberts makes a convincing argument for aiming to achieve both long and short objectives within the same execution. It is a creative challenge but he recommends an approach that delivers both the emotional impact and the rational product arguments that activate sales performance. His example is Bendigo bank and its current advertising campaign, which aims to deliver both a sense of anger at the dominant, lazy status quo of Australia’s ‘big four’ banks and then segues into a strong product and price offer.

It’s a convincing argument. But one that also has drawbacks. The Bendigo ad in question is well executed but it looks and feels like a bit of a camel. Its emotional message is stunted and underwhelming. Its call to action is also muffled and less direct than it could be. Field and Binet have always admitted that the long drives the short and the short delivers on the long. But they also make the argument, with data, that when you try and do both within the same execution these “double duty” ads usually underperform competitors that opt for a simultaneous or sequential approach.

All three alternatives should be on the table as practical, well trained marketers try to actually deliver on the fabled benefits of long and short marketing. Strategy is about making a choice, but it’s also about making that choice based on the contextual factors that surround a brand. I can see arguments for and against all three different funnel juggling approaches. Put them all on the table.

Because after you get the theory of the long and short of it, there comes the even trickier challenge of ‘the deciding and the executing of it’.