Marketers must be included when competition lawyers test Google’s market power

When Google’s market power is being assessed, Google and its customers can’t be the only marketing voices being heard – other marketing experts must be brought to the table.

The competition cases against Google are the biggest legal battle marketing has ever seen. How they are resolved will decide the choices marketers have for decades to come. Everyone with a marketing budget will be affected.

The competition cases against Google are the biggest legal battle marketing has ever seen. How they are resolved will decide the choices marketers have for decades to come. Everyone with a marketing budget will be affected.

And it’s possible the lawyers and economists involved are missing something.

Evidence has been accumulating on the marketing frontlines that search ads often don’t do the same thing that other advertising does. Other advertising builds demand, while search often acts to make products available online.

This is directly relevant to the question of whether Google has market power.

If search ads can be substituted with other media channels, Google is a big – but not huge – media owner in a landscape also populated by broadcasters, radio stations and owners of poster hoardings.

But if they do a different job, one that other channels can’t do, Google is dominant in a search-only market and vulnerable to having its activities restricted under competition law.

The acid test

To test whether Google competes with other media channels, economists will analyse what happens when the price of Google search ads go up by 5-10%.

If marketers keep their budgets with Google and accept fewer clicks, or spend more to maintain volumes, it shows that there’s an absence of serious competition. That there are no other media choices that are close substitutes for Google search ads. That Google is free to increase prices and make more profits at the expense of advertisers.

Search data is a gold mine for marketing strategy

In the cases, a lot of effort will go into analysing real-world data. Economists will look at instances of increasing prices and analyse the response. No doubt the short answer will be that it’s different in different circumstances. Understanding the complexity and coming to an overarching conclusion will take years.

But this is not just a question for economists and lawyers. It’s a question for marketers – both those who spend marketing budgets and those who study marketing and offer advice.

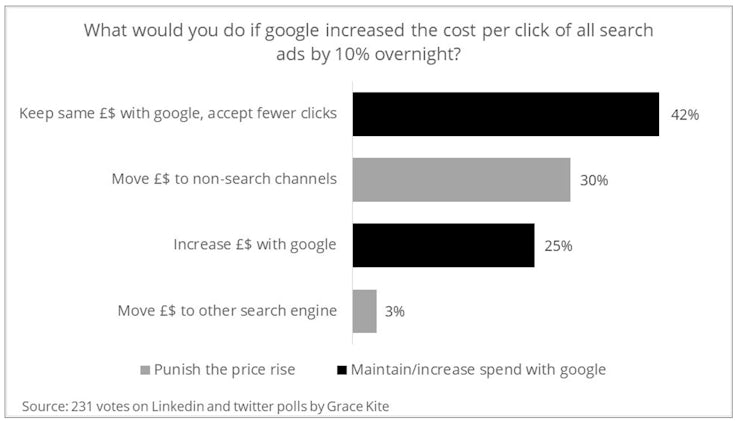

And many do feel able to comment. The chart below shows the results of a polling exercise on social media that asked the ‘what if?’ question.

What’s striking is that two-thirds of marketers (in the black bars) would either maintain or increase spending with Google.

What’s striking is that two-thirds of marketers (in the black bars) would either maintain or increase spending with Google.

In explaining why, marketers often listed a range of things they’d do before taking money out of Google. They’d look for better value keywords, wait, try to game the auctions, revisit business goals and even start website initiatives to improve the conversion rate of the now more expensive clicks.

Others said that in their circumstances there is no other option but to ‘take it on the chin’ or ‘suck it up’.

It’s a set of results that’s certainly suggestive. But beware, if the economists and lawyers were looking at this poll, they would say the third of people who would move their money are important. Their existence, and the loss of their spend, might be enough to prevent Google from profiting by price rises. The only way to tell is to examine Google’s finances.

Search often does a different job to other channels

If there is a feeling among the majority of frontline marketers that Google ads are an essential part of marketing plans that can’t be replaced, experts and academics already have a theory and supporting evidence as to why.

The theory is Byron Sharp’s. It says that most advertising is about mental availability – building and refreshing memory structures that make it easy to think of the brand – but that search mostly does a different job. Search ads are about physical availability, enabling people to actually get hold of the product being sold.

The argument goes that in these cases search ads are the online equivalent of a signpost pointing to a real-world shop, or the cost of maintaining physical buildings and shelf space. They’re not an investment into future sales, but a cost of current online transactions that has to be paid.

And the evidence to support this theory has been mounting up.

Since the mid-noughties, the increase in spending on search advertising is highly correlated with the increase in penetration of ecommerce. Correlation is not causation, but one possible explanation is that ecommerce businesses need online signposts.

Then, in 2020, when physical shops were often shut, and economies in recession, global advertising budgets fell by 20%, but search actually increased by 26%, according to the IAB. It’s because even distressed businesses had to sell online to survive, and if you want to do that, you need search ads.

Academics have also contributed evidence. In a study focussing on a search switch off in a large US services firm and its biggest competitor, there was no significant impact on the competitor. The conclusion was that search is often “navigational” in that people use it to navigate to ecommerce sites instead of entering a URL.

And finally, there’s the evidence that brought me to this issue. Behind NDAs, market mix models often show that search advertising doesn’t drive new sales, but at the same time, performance marketing teams see that when it is switched off some sales are lost. Reconciling these two pieces of evidence means concluding that search does an important job, but it isn’t the same one that traditional advertising does.

If it’s about marketing, marketing experts must be consulted

The evidence above is not sufficient to conclude that Google has market power. A lot more research and analysis is needed.

What is clear, though, is that Google and its customers cannot be the only marketing experts in the room when these things are assessed.

So far, Byron Sharp and his team haven’t been consulted. They should be. Likewise, independent experts with experience executing and evaluating real-life marketing plans need to be at the table.

This post was written by Dr Grace Kite and Dr Luke Wainscoat. Luke is a competition and regulatory economist at HoustonKemp.